Fire-Starting

Archaeologist don’t really know when man started making his own fires; some estimates go back as far as a half-million years, other as recent as 200,000 year ago. Whenever it was, it is unquestionably one of the most important things we’ve ever done as a species. Though fire is fairly simple to understand in terms of what does it take to make a fire, the process is more challenging than you might think. You need three things: heat, fuel and oxygen. When these three elements are brought together correctly, you have fire.

Before trying to make any fire you need to assemble materials to ensure that you can get it going. Prior to adding some form of combustion, you need to make sure that you’ve got what you need to not only start the fire, but keep it going once lit. Basically we’re talking about: tinder piles, specialized “fire starters”, small combustibles like leaves, sticks, bark or whatever is lying around that is dry and can easily be ignited. You to learn what kind of barks that you can use and how to prep them, and even familiarize yourself with specialized wood types (like fatwood) which give you a better chance to start and maintain a good fire. Learn how to make feather sticks and tinder bundles. Be sure to have a sufficient supply of wood to burn post-ignition. It’s not a smart idea to go to all the work to get the thing going only to have it die of fuel starvation. It’s also a good idea to learn some tips & tricks of wood collection, such as breaking off small limbs from dead trees to keep from getting wet wood off the ground or using forks on trees to break dead branches into shorter lengths to fit in/on your fire.

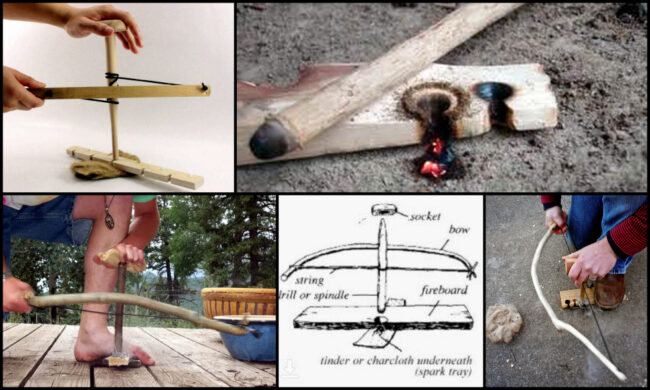

Man’s first experiences with fire were when they occurred in Nature; lightning strikes, wildfires, materials caught on fire by lava flows, etc. But, when man started making his own, it was almost a guarantee that it was by some form of friction. There are a couple that come to mind; the first being the simple rubbing of a stick on another piece of wood, eventually creating enough heat for combustion; an exhausting and time-consuming process. If you ever saw the movie “Cast Away”, you saw Tom Hanks trying this exact procedure. Somewhere down the line somebody figured out that if you got a stick, ran a string between the ends and bent it into a bow that you could use that bow to accelerate the process and make fires much more easily. Don’t get me wrong, it’s still a pretty labor-intensive method, but it’s much easier than the earliest system. Today you’ll find a bunch of folks still doing this, especially people who are into Bushcrafting and Survival. With this method, you can find pretty much everything you need in the woods, or to expedite the process you can use a shoestring or any kind of cordage. In a pinch you can even use vines or grasses to make something to use between the ends of your bow.

Matches are the next evolution of fire-starting and those date back to around 1200 A.D. according to historians. The type we use today are of a more modern design, but basically they’re all the same. The biggest differences in matches of today are the sizes, styles, special coatings and burn duration. There are so many specialty matches out there that I could write a short novel on them. Suffice it to say, whether you’re using a simple wooden kitchen match, Hurricane or Storm matches, or even a liquid-chemical match; they all require the same starting mechanism, which is friction or sparks. You basically contact the match head with something that creates heat, or in the case of the liquid matches; a spark. Burn times vary from just a second or two (like paper matches) to several seconds, and some can even burn in the rain and with high winds.

It wasn’t until the early 1800s that “lighters” as we know them were invented. Once again a pretty simple system; put some flammable liquid into a container of some sort, add a wick and finish off with something that’ll create a spark to ignite the liquid. In recent years, manufacturers have added flammable gasses to the offerings in the lighter department. The most common and well-known liquid lighter by brand name is ZIPPO. The most common butane lighter is BIC. I think it’s safe to say that almost everybody has heard of one of the other. There are some very high-end models that can operate in almost any weather conditions, but you will pay dearly for those.

The next category of fire-starters are the metallic variety; primarily magnesium or Ferro rod. With magnesium fire-starting, you basically scape or lay down a small pile of the material and add a spark to ignite it. With a Ferro rod setup you prepare a tinder pile, draw steel across a Ferro rod, creating a spark igniting the pile. While these methods aren’t generally considered as convenient as a match or lighter, in the hands of the right person they almost as easy. One huge advantage to these systems is that you can get a tremendous number of fire starts from either one, sometimes in the thousands of starts with a single piece of gear.

If you’re headed out into the Wild, fire-starting is without question one of the most essential skills you need to learn. If you can build a shelter and make a fire, you stand a much better chance of survival. A fire is your best ally to prevent hypothermia, purify water, cook food and if nothing else, make you feel better at the end of a long day. One last word on this, I have found countless videos on YouTube that show you methods for fire-starting and related subjects. I try to watch some every day, and every time I do, I learn something new. You can never have too much knowledge when it comes to surviving and enjoy the Great Outdoors. It’s a lifelong education, and a fun one at that.

Last modified on: January 5th 2023.